For Friday AI Fun, let’s look at an oldie but goodie: Google’s Quick, Draw!

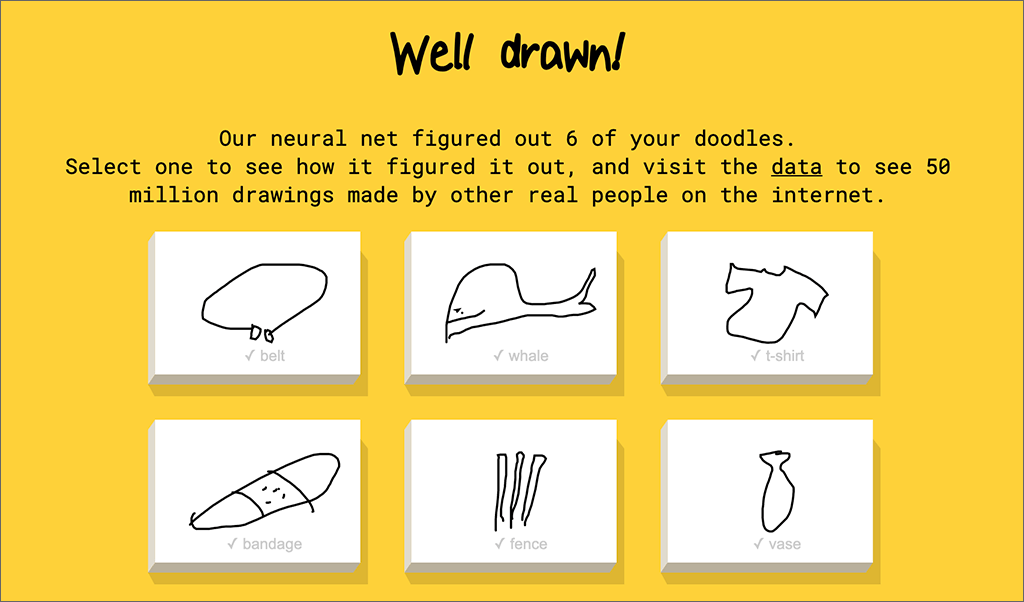

You are given a word, such as whale, or bandage, and then you need to draw that in 20 seconds or less.

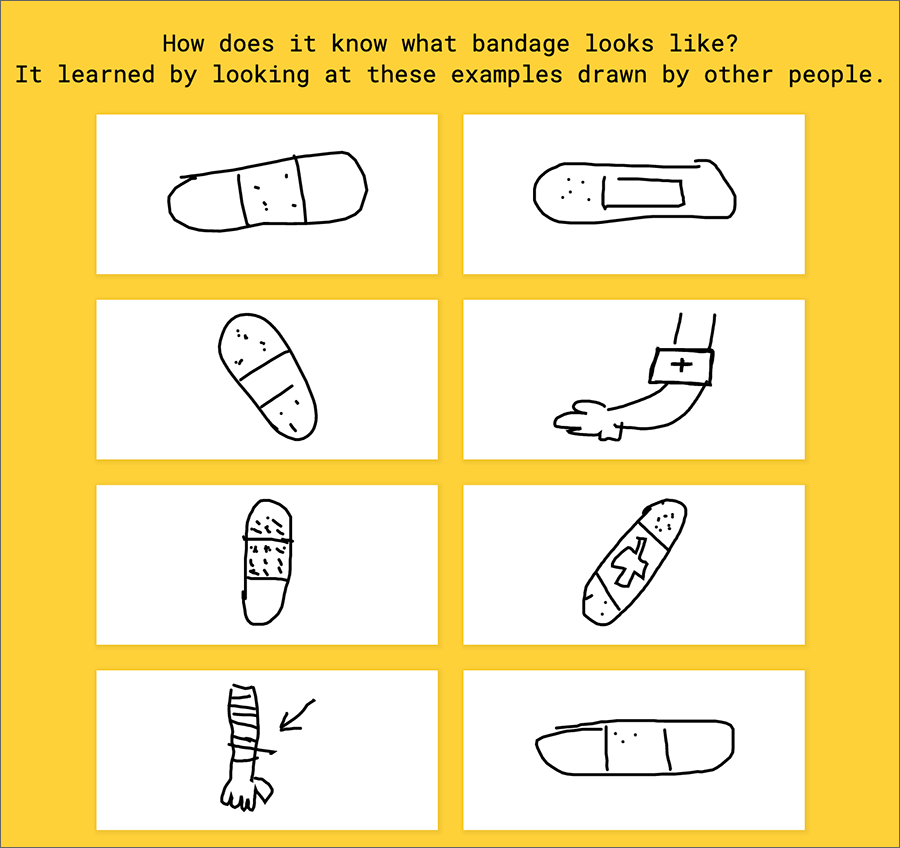

Thanks to this game, Google has labeled data for 50 million drawings made by humans. The drawings “taught” the system what people draw to represent those words. Now the system uses that “knowledge” to tell you what you are drawing — really fast! Often it identifies your subject before you finish.

Related: Ask a computer to draw what it sees.

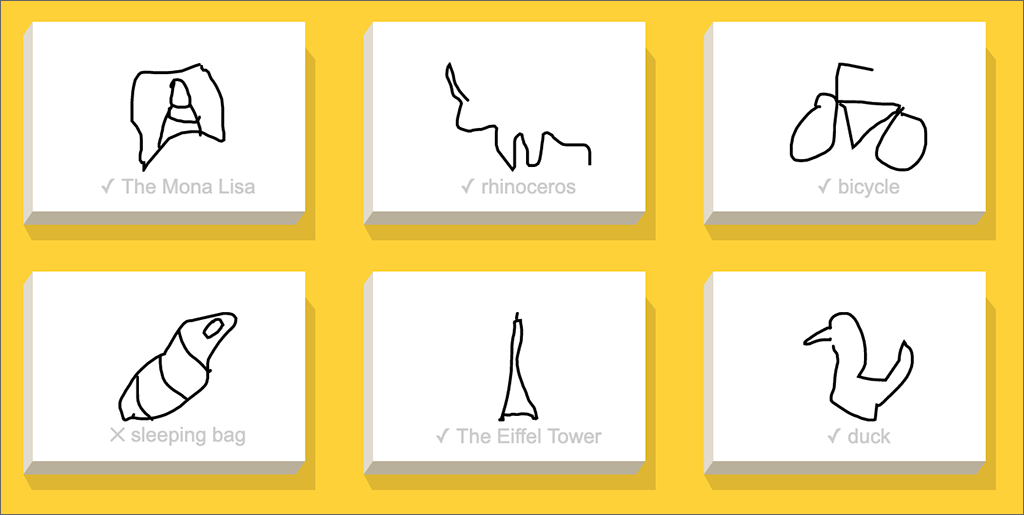

It is possible to stump the system, even though you’re trying to draw what it asked for. My drawing of a sleeping bag is apparently an outlier. My drawings of the Mona Lisa and a rhinoceros were good enough — although I doubt any human would have named them as such!

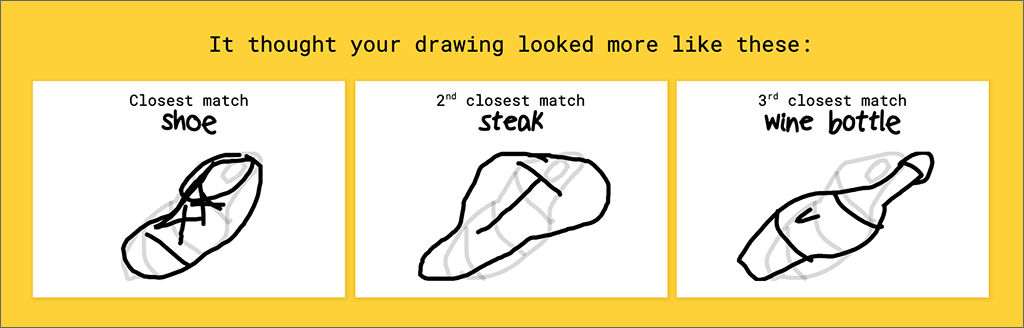

Google’s AI thought my sleeping bag might be a shoe, or a steak, or a wine bottle.

The system has “learned” to identify only 345 specific things. These are called its categories.

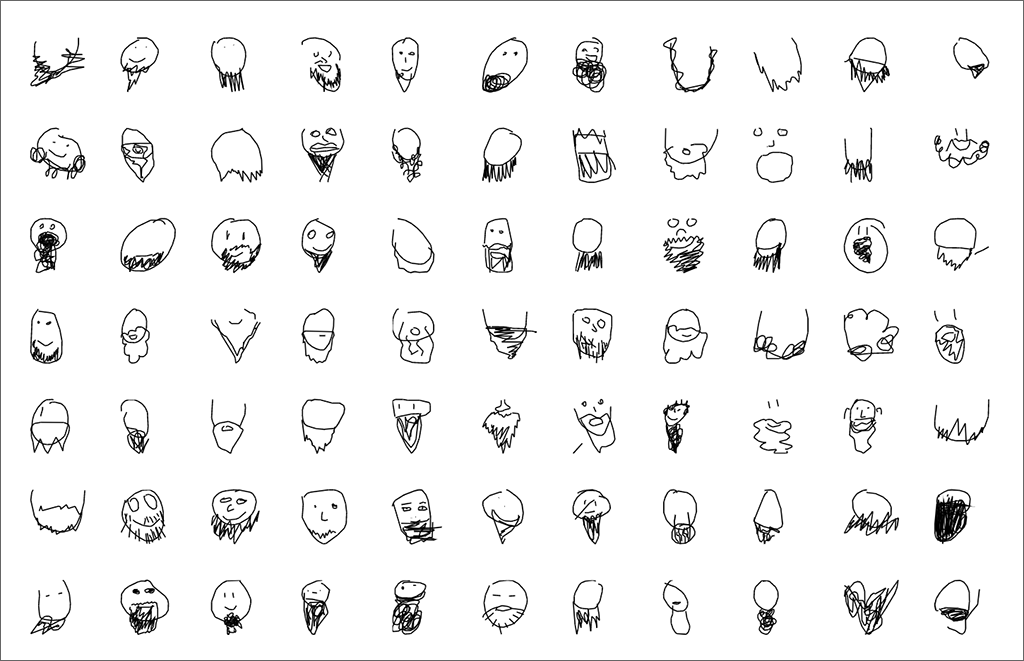

You can look at the data the system has stored — for example, here are a lot of drawings of beard.

You can download the complete data (images, labels) from GitHub. You can also install a Python library to explore the data and retrieve random images from a given category.

AI in Media and Society by Mindy McAdams is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Include the author’s name (Mindy McAdams) and a link to the original post in any reuse of this content.

.