A common use of machine learning is to train a model to identify a particular kind of document, or a particular characteristic in a document — and then sort a gigantic set of documents. This produces a much-reduced subset of all documents that match the desired criteria. There might be some false positives in the subset, but it still gives researchers or journalists a big jump forward by eliminating thousands of unwanted documents.

This kind of sorting goes well beyond a simple search for keywords.

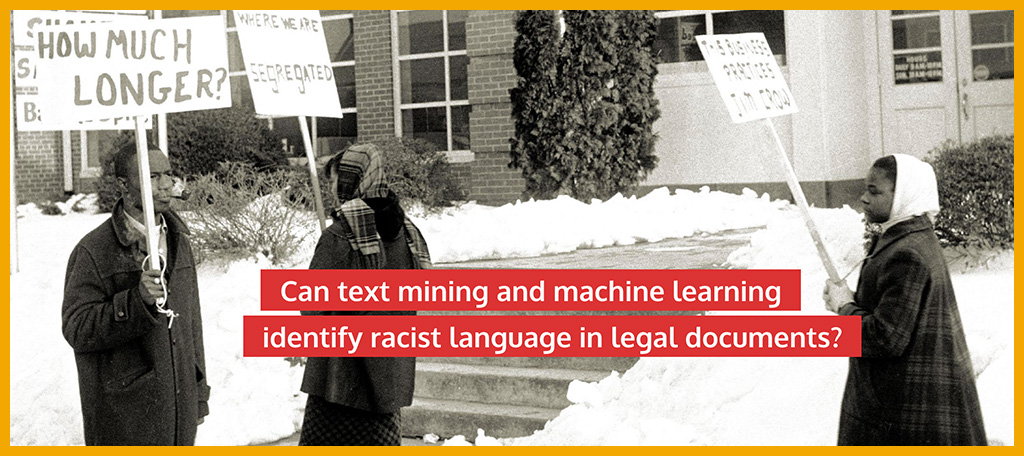

A great example has emerged from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. On the Books: Jim Crow and Algorithms of Resistance is a project that includes a public plain-text collection of North Carolina laws (1866–1967) likely to be Jim Crow laws.

There is a public GitHub repo of the code used in this project. It includes a full walkthrough of the project’s workflow — data acquisition and cleaning, OCR, unsupervised and supervised classification, etc.

The base document set (the main corpus) consists of 96 volumes, with 53,515 chapters, having 297,790 sections (source).

The project’s title gives homage to Safiya Noble’s 2018 book Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism.

“State-based racial segregation laws were incredibly inconvenient, irregular, and, most importantly, unconstitutional.”

—William Sturkey, Ph.D.

A historical perspective on this data collection was provided by William Sturkey, a history professor at UNC, in “On the Books”: Machine Learning Jim Crow (September 2020). He says On the Books is “the first and most complete collection of all Jim Crow laws from a single American state.” He points to the difficulty of cataloging and studying all Jim Crow laws from any state “because there were just so many.”

AI in Media and Society by Mindy McAdams is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Include the author’s name (Mindy McAdams) and a link to the original post in any reuse of this content.

.